Domas Valancius was born in Pauosniai village, Plunge district, Lithuania, on 21 June 1922, to peasant parents Jonas and Ona Valancius. Ona’s maiden name was Grismanauskaite.

Domas’ name was Dominykas on the birth record, but he probably chose the shorter version of Domas to make it easier to say and spell. English language equivalents would be Dominic for Dominykas and Dom for Domas.

|

| Domas Valancius' birth record on 21 June 1922, in Plunge church, Lithuania |

From an Arolsen Archives record, we know that Domas Valancius was in the British zone after World War II ended. During the War, from 6 December 1943 to 31 March 1945 he had worked for the Gerwerkschaft Dorn in Herne, Germany. The Gerwerkschaft Dorn produced screws, nuts and rivets for the mining industry, the railways and the bridge, ship, wagon, vehicle and agricultural machinery construction industries. It is highly likely that Domas had not volunteered for this work but had been sent to it under some form of military escort.

|

| The entrance to the Gerwerkschaft Dorn on Dornstraße in 1921 Source: Herne von damals bis heute |

Domas appears to have been interviewed twice about his interest in resettling in Australia, on 6 and 10 October. The form used for his 6 October interview did not ask him about his education, but it did ask for his occupation and the length of time for which he had been engaged in this. The interviewers recorded that he was a factory worker who had been doing this type of work for 4 years.

At the time of the interview, he was living in a Displaced Persons’ camp in Solingen, about one hour’s drive south of Herne. If he was working still in a factory, it was quite likely to be one in Solingen, famous since mediaeval times for the manufacture of blades, starting with sword blades.

The form did ask for Domas’ previous occupation, to which the typed answer was ‘nil’. This suggests that he was student whose studies, like those of so many others, were interrupted abruptly by the German military seizing him to work for them. At least it was a factory in his case, not digging ditches under fire.

The 10 October form did ask about his education, which elicited a ‘4 years of primary school’ answer, basic for a Lithuanian of Domas’ age. If you knew that Australia was looking for labourers, you would not want to boast about your higher education. Perhaps that is why Domas did not give more information.

|

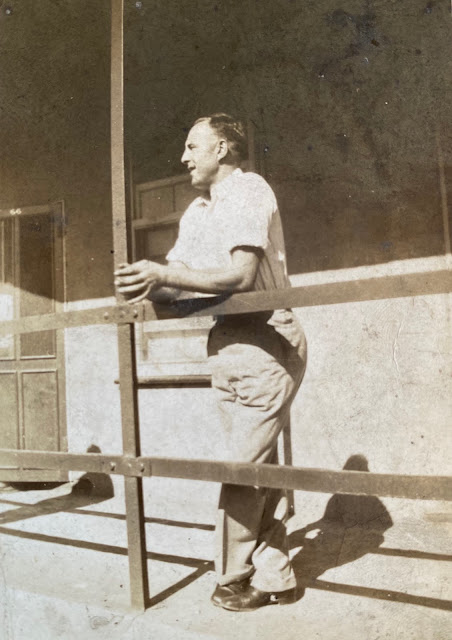

| Domas' identity photo from his selection papers Source: NAA: A11772, VALANCUS DOMAS |

He left Bremerhaven for Australia with 842 other Baltic refugees on the USAT General Stuart Heintzelman on 30 October 1947 and on 28 November 1947 he arrived to Australia.

From the General Heintzelman nominal rolls of passengers it is known that Domas’ last place of residence in Germany was in the city of Lintorf. His Bonegilla card noted that he had a fiancee, Loni Klingbeil, who was living in Wuppertal-Hammerstein, Germany.

Domas’ first job in Australia was in Western Sawmilling Pty Ltd, in Rylstone, NSW. He left Bonegilla camp on 20 January 1948 for Rylstone. This is still a small town on the western side of the Great Dividing Range, behind Newcastle. Only 3 men were sent to this employer, the other 2 being Rasa’s grandfather, Adomas Ivanauskas and an Estonian, Leonard Jaago.

Leonard must have felt put out if the two Lithuanians started to talk to each other in their native tongue, but at least he could ask them in German to tell him what they were discussing.

Domas was being paid a wage of £6/2/6 per week, more than some others were getting in their new jobs. He and Adomas might have found the work or the management disagreeable, though, because they returned to the Bonegilla camp on 12 April 1948. Maybe the volume of work had run down. Regardless of Domas’ and Adomas’ reasons, Leonard stayed behind at Rylstone.

The Commonwealth Employment Service (CES) staff in the camp knew immediately what to do with the two returning men. They were added to the group being sent 3 days later to Iron Knob in South Australia to work with a company then known as Broken Hill Proprietory Limited – but now simply BHP.

The group of 12 included Romualdas Zeronas, about whom we have written already for this blog. Rasa thinks that Domas and her grandfather would have become friends by now, especially as they left Rylstone together, and they would have included Romualdas in their friendship.

A new paper, Australijos lietuvis, carried a notice about supporting it with donations of money on 12 September 1948. The group of Lithuanians working in the Iron Knob mines immediately understood that they needed to help. After receiving their wages, they put together a pile of money and sent it to the newspaper. One of them was Domas Valancius, who donated 5 shillings.

Domas had first written to the Minister for Immigration about sponsoring his fiancé to move to Australia on 10 February 1948, that is, just over 2 months after arriving at the Bonegilla camp and 3 weeks after leaving it for Rylstone. A file was raised for the first letter and any ensuing correspondence, as was normal Australian Public Service practice. The existence of this file means that we have a report from the Port Augusta District Employment Officer to his superior in Adelaide, dated 21 September 1948, about Domas and another Lithuanian from the First Transport, Petras Juodka.

The Employment Officer, EJ Puddy, wrote that he had travelled to Iron Knob following a phone discussion with the Registrar of the Broken Hill Proprietory Limited company. There he had first talked with Broken Hill’s Iron Knob foreman. Both Domas and Petras were said to have ‘given quite a lot of trouble on and off the job’.

Both had been before the Iron Knob court where they had been fined for disorderly behaviour in a public place. This had been the result of a brawl in Broken Hill’s mess rooms. It is interesting that a privately owned place was considered a public place for the purpose of the court appearance, unless the brawl continued on a public road outside.

Puddy reported that the foreman had told him that Domas was ‘of an argumentative and repulsive nature’. Domas was considered the leader with Petras a follower, despite Petras having been before the local court one more time than Domas. The foreman thought that Petras would settle down if separated from Domas.

The local policeman told Puddy that he thought it would be necessary to transfer both of the men ‘as there appeared to be a feeling amongst others that there was trouble ahead.’

Puddy and the foreman then interviewed the two men together. Puddy wrote that Petras ‘was very repentant, but (Domas) did not appear to care what happened to him’.

The company agreed to give the men one week’s notice and told them that they would have to pay their own fares to Adelaide in order to visit the CES there. Their ‘services were terminated’ on 23 September.

A handwritten note from an official using initials only reports that Domas, saying that he wished to return to Germany, had caught the express train eastwards on the night of 25 September. He had stated that he was returning to the Bonegilla camp. The purpose of the note was to instruct others to take no further action on Domas’ wish to sponsor his fiancé to Australia until they knew more about his plans.

And that what appears to have happened. There was no further action, although Domas had found a guarantor for Loni among his Australian colleagues at Iron Knob. He did not, however, meet the basic requirement of having been resident for at least 12 months before sponsoring. By persisting in finding a guarantor, he showed no sign of understanding the residence requirement, which had been explained by letter. He was advised also that someone else would have to find the money to pay for Loni’s passage, since apparently she was not a Displaced Person. In all of this frustration, Loni might have found another special friend anyhow.

Domas arrived at the Bonegilla camp for a third time on 27 September. On 8 October, the Bonegilla camp’s Assistant Director signed a note to the head Immigration official for South Australia, reporting the arrival and stating that a report on Domas also had been sent to the head office of the Immigration Department. The files on Domas which have been digitised so far do not contain that report. It might still be waiting to tell us more about how Australian officials saw Domas on a Central Office file about Bonegilla activities.

This time it took the CES staff nearly one month to find another job for him. On 26 October, he was sent to Standart Portland Cement Company Limited, at Brogans Creek, NSW. That’s probably a typing mistake for ‘Standard Portland Cement’.

On Domas’ Bonegilla card, Brogans Creek is described as ‘near Charbon’. Charbon is a tiny village 17 kilometres north of Brogans Creek by road. It is interesting to note that Domas’ original destination, Rylstone, is only 25 kilometres north by road. Geographically, Domas was back almost where he had started in Australia.

In June 1949, a newspaper called the Mudgee Guardian and North-Western Representative carried, in its ‘Rylstone and Kandos News’ columns, a report from the Kandos Court of Petty Sessions. Two Lithuanians, Domas Valancius and Bronius Latrys were fined on 25 May for ‘behaving in an offensive manner’. Domas was fined 10 shillings with 10 shillings costs while Bronius lost £2 with 10 shillings costs.

Clearly the two were not drunk, or they would have been charged with a difference offence, like ‘drunk and disorderly’. One legal firm gives as examples of offensive behaviour, ‘yelling, swearing, urinating, pushing and shoving or being part of an aggressive or rowdy group’. This must be in or near a public place or school.

Having received the larger fine, Bronius, whose family name actually was Latvys, probably was the noisier of the two. As he was 10 years older than Domas, perhaps he thought that he had the right to yell at Domas and the latter yelled back.

Kandos is a small town only 6 kilometres south of Rylstone and 3 kilometres north of Charbon. As of the 2021 Census, its population was 1263. While Domas had stayed at Iron Knob for only 5 months, it looks like he was still with the Portland Cement company after 7 months.

Less than 3 months later, Domas was before the Kandos Court of Petty Sessions again. This time he had been drinking and, according the arresting and prosecuting Sergeant of Police, using such bad language that the Mudgee Guardian and North-Western Representative refused to print it.

The Lithgow Mercury of 1 September 1949 also found the story interesting enough to reprint it. It could see a humourous side to Domas’ behaviour on the night of 12 August, when Domas was caught easily because he had fled into a fowl yard.

,%20Thursday%201%20September%201949,%20page%206.jpg) |

| The Lithgow Mercury reports on Domas, 1 September 1949, page 6 Source: Trove (Click image to view in another tab and enlarge to read) |

The absence of further court reporting does suggest that Domas adhered to his promise not to drink alcohol. He had also been with Standard Portland Cement for 10 months, and perhaps was about to be released from his obligation to work in Australia shortly, at the end of September 1949.

He was in the news again in March 1953, having moved from inland of Newcastle, an industrial city north of Sydney, to the vicinity of Wollongong, another industrial city but south of Sydney. The bicycle he was riding near his Port Kembla home was hit by a car. He suffered head injuries and abrasions to the face. He was taken to the Wollongong Hospital.

Or was he on a motorcycle? That was how another newspaper reported the incident.

He acquired Australian citizenship on 24 January 1961. He was still living at Port Kembla, but at a different address. His addresses now could be followed on electoral rolls. In 1963, he was still at his 1961 address. By 1968, he had moved again but still was very close to his 1961-63 address. After that, electoral rolls have not been digitised.

Searching the Ryerson Index for any Valancius death notices reveals only one. It is that of Domas, who had died on 12 May 1980 in the Bundanoon district of NSW. He had moved inland again, southwest of Port Kembla.

Domas was only 57 years old at the time of his death.

Whoever was the executor of any estate that Domas left did not realise that he had taken out a life insurance policy. That is why his name was included in a list of unclaimed money published in a Commonwealth of Australia Gazette 7 years later, on 29 June 1987.

Anyone who has a life insurance policy is unlikely to have died without leaving a will, so there must have been an executor. We have to hope that any money due to Domas or his heirs found its way to its rightful place.

Sources

Lithuanian State Historical Archives, Rietavo dekanato bažnyčių gimimo metrikų knyga, 1922-01-01 – 1922-12-31 [Birth register of churches in the Rietavas deanery, 1922-01-01 – 1922-12-31] https://eais.archyvai.lt/repo-ext-api/share/?manifest=https://eais.archyvai.lt/repo-ext-api/view/267502635/297161654/lt/iiif/manifest&lang=lt&page=195 [Domas Valancius’ birth record in Plunge church is on page 174, record number 107].

Arolsen Archives, City region of Herne: Report on Employed Foreigners, Category A, Lithuanians, Documents from Australijos lietuvis (1948) ‘Pirmieji Mūsų Rėmėjai’in Lithuanian [‘Our First Sponsors’], 12 September, page 10, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/280321942 accessed 30 January 2025.

Bonegilla Migrant Experience, Bonegilla Identity Card Lookup, Domas Valancius https://idcards.bonegilla.org.au/record/203712436 accessed 30 January 2025.

Commonwealth of Australia Gazette (1961) ‘Certificates of Naturalization’, Canberra, 6 July, p 2556, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/240889446/26005562 accessed 30 January 2025.

Commonwealth of Australia Gazette (1987) 'Life Insurance Act 1945 — Unclaimed Money', Canberra, 29 June, p 318 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article239979262 accessed 28 January 2025.

Goulburn Post (1980) ‘Death Notices’, Goulburn, NSW, 13 May

Herne von damals bis heute, Schraubenwerk Dorn, Ein Schwimmbad als Zeichen des Erfolges [Herne from then to now, Dorn Union, A Swimming Pool as a Sign of Success] https://herne-damals-heute.de/bergbauindustrie/zuliefererbetriebe/schraubenwerk-dorn/ accessed 25 February 2025.

Illawarra Daily Mercury (1953) 'Cyclist Hurt in Collision' Wollongong, NSW, 17 March, p 7 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article134041121 accessed 25 February 2025.

Lithgow Mercury (1949) ‘Portland Section, Balt Migrant “Turns it on” at Kandos’, Lithgow, NSW, 1 September, p 6 (City Edition), http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article220833346 accessed 25 February 2025

Mudgee Guardian and North-Western Representative (1949) 'Rylstone And Kandos News' Mudgee, NSW, 2 June, p 9 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article156448258 accessed 25 February 2025

Mudgee Guardian and North-Western Representative (1949) 'Kandos Court of Petty Sessions: Lithuanian Sentenced to Hard Labor', Mudgee, NSW, 25 August, p 10, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article156449257 accessed 25 February 2025

National Archives of Australia: Migrant Reception and Training Centre, Bonegilla [Victoria]; A2571, Name Index Cards, Migrants Registration [Bonegilla], 1947-1956; VALANCIUS DOMAS, VALANCIUS, Domas : Year of Birth - 1922 : Nationality - LITHUANIAN : Travelled per - GEN. HEINTZELMAN : Number – 875, 1947-48; https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/ViewImage.aspx?B=203712436 accessed 26 February 1925.

National Archives of Australia: Department of Immigration, Western Australia; PP482/1, Correspondence files [nominal rolls], single number series, 1926-52; General Heintzelman — arrived Fremantle 28 November 1947 — nominal rolls of passengers, 1947–52, page 16 https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/ViewImage.aspx?B=439196 accessed 28 January 2025.

National Archives of Australia: Department of Labour and National Service, Central Office: MT29/ 1, Employment Service Schedules; Schedule of displaced persons who left the Reception and Training Centre, Bonegilla Victoria for employment in the State of South Australia - [Schedule no SA1 to SA31], page 49 https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/ViewImage.aspx?B=23150376 accessed 30 January 2025.

National Archives of Australia: Department of Immigration, Central Office; A11772, Migrant Selection Documents for Displaced Persons who travelled to Australia per General Stuart Heintzelman departing Bremerhaven 30 October 1947, 1947-47; 500, VALANCUS (sic) Domas DOB 21 June 1922, 1947-47 https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/ViewImage.aspx?B=1834240 accessed 26 February 2025.

National Archives of Australia: Department of Immigration, South Australia Branch; D4881, Alien registration cards, alphabetical series, 1947-76; VALANCUS (sic) DOMAS, VALANCUS (sic) nDomas - Nationality: Lithuanian Arrived Fremantle per General Stuart Heintzelman 28 November 1947, 1947-48 https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/ViewImage.aspx?B=7174218 accessed 26 February 2025.

National Archives of Australia: Department of Immigration, South Australia Branch; D401, Correspondence files, multiple number series with 'SA' prefix, 1946-49; SA1948/3/512, VALANCUS Domas - application for admission of relative or friend to Australia - KLINGBEIL Loni, 1948-53 https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/ViewImage.aspx?B=12455258 accessed 26 February 2025.

Ryerson Index, Search for Notices https://ryersonindex.org/search.php accessed 25 February 2025.

South Coast Times and Wollongong Argus (1953) 'Works' Accidents', Wollongong, NSW, 19 March, p 15 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article142719599 accessed 25 February 2025.

W&Co. Lawyers, ‘Behave in an Offensive Manner’ https://wcolawyers.com.au/behave-in-an-offensive-manner-nsw/ accessed 25 February 2025.

Wikipedia ‘Solingen’ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Solingen accessed 25 February 2025.