Updated 15 August 2025.

One quarter of male Baltic refugees from the First Transport were employed as fruit pickers in Victoria’s Goulburn Valley between January and March 1948. The Commonwealth Employment Service’s District Office had arranged for them to assist in the fruit harvesting subject to certain conditions, including that they be employed in batches of at least five and that satisfactory board and accommodation had to be provided by the growers.

The Goulburn Valley had only a small quantity of available labour which would have been totally inadequate to harvest the crop. This would lead to the loss of thousands of pounds worth of fruit. Most of the refugees, whose average age was 24 years, were employed in the Ardmona area for the harvesting of fresh fruit, canning fruit, and dried fruits.

Apricot picking had started early in January, before the Baltic refugees were made available. The pear picking season was expected to start on 20 January.

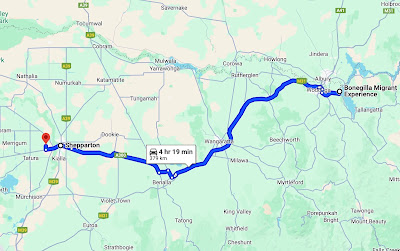

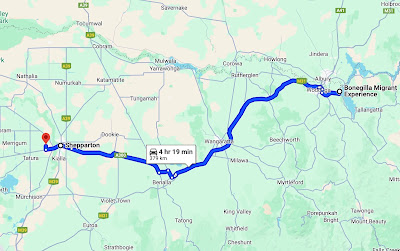

On Wednesday and Thursday, 28-29 January 1948, 193 Baltic migrants arrived in Shepparton by special buses from the Bonegilla Migrant Camp. The 193 number is that given by the Shepparton Advertiser newspaper on 30 January: it’s more optimistic than the 187 we found by examining all the “Bonegilla cards” for the Heintzelman group.

|

The red dot in the west (right) of this Google map marks Ardmona; the Bonegilla Migrant Experience in the east (left) of this map has been developed from the former Bonegilla migrant camp: the modern trip from Bonegilla to Shepparton takes a little more than two hours so the remaining two and a quarter hours is the trip from Shepparton to Ardmona;

Click on the map for a larger version on another page

Source: Map data © Google |

The Advertiser journalist wrote that the Goulburn Valley fruit growers were almost unanimous in agreeing that the new workers from the Displaced Persons camps were an “excellent type” and they were “well satisfied with the selection”. The refugees were to be distributed among 30 orchards in the Shepparton and Ardmona district. Maybe plans had changed since destinations for the fruit pickers were recorded at Bonegilla, since they show only 16 employers.

The journalist advised that, at the end of the season, the new workers would be free to accept employment as permanent orchard hands if they so desired. Wishful thinking!

The 16 orchards involved were those of :

Anton Lenne of Ardmona,

AW & JF Fairley of Shepparton,

Bruce Simson of Ardmona,

Dundas Simson Pty Ltd, Ardmona,

E Fairley of Shepparton,

HE Pickworth of Ardmona,

H Hick of Grahamvale,

I Pyke of Ardmona,

J Nethersole & Sons of Ardmona,

JT Goe of Orrvale,

RT Clements of Toolamba,

SF Cornish of Ardmona,

TE Young of Ardmona,

Turnbull Bros of Ardmona,

VR McNab of Ardmona, and

W Young of Kelvin Orchards, Ardmona.

As for the minimum group size, the Advertiser mentions 3 and that was the number that the Bonegilla cards show going to JT Goe. They were one Latvian and two Lithuanians, who we have to hope were already great friends. At least they had German as a common language.

|

Picking pears, possibly on the Grahamvale property of Mr H Hick

Source: Arvids Lejins collection |

It seems that not all orchard owners were fair to the new workers. According to the Communist Party’s Tribune newspaper, some were kept in isolated groups and were working a 48-hour week for the same pay as Australians receive for a 40-hour week. Some of the Balts had thrown in their jobs and returned to Bonegilla early.

Povilas Laurinavičius, who we met in the last blog entry, returned to Bonegilla after 2 weeks only with Anton Lenne of Ardmona. We don’t know why he returned. It could have been the hours expected to be worked 6 days a week. Maybe the outdoor conditions in February heat did not suit him, give that he was 40 years old already. If that was the reason, it wasn’t taken into account when he was sent a few days later to the Iron Knob mine in South Australia. Antanas Jurevicius returned from Anton Lenne on the same day. According to Antanas' Bonegilla card, he had been married in the camp on 22 December, so he probably was keen to get back to his new bride.

|

Anton Lenne: photograph provided by Marg Spowart to the

Lost Mooroopna Facebook page

|

Eleven had returned already before these two, the first 6 on 11 February, so after 12 days only at the most working in their new industry. Five had been working for J Nethersole and Sons, Ardmona, and one for Mrs I Pyke.

|

Fruit pickers' lunch break, possibly on the Grahamvale property of Mr H Hick

Source: Arvids Lejins collection |

A small number of the fruit pickers could not cope with their new-found freedom. Jonas Razvidauskas appeared before the Shepparton Court on 16 February charged with assault, after he had attacked 3 policemen in the Shepparton Police Station and broken the glasses of one. He was yet another First Transport man who had had too much to drink, having bought a bottle of wine and consumed it all, after which he could not remember anything.

He was said to have torn his own clothes to shreds and to be appearing in clothes borrowed from another prisoner. He was fined £2 on each of the assault charges and ordered to pay £2 to replace the broken glasses. This was a total of £8, likely to be more than he was earning each week. He was one of the employees of Turnbull Brothers of Ardmona, and was one of those sent on to Goliath Portland Cement in Railton, Tasmania afterwards.

The Melbourne Sun News-Pictorial newspaper reported an outline only of Razvidauskas’ behaviour in the Police Station but the local newspaper, the Shepparton Advertiser, went into considerable front page detail about the aggression and damage.

It reported also that 2 more of the men appeared before the Court. Another Lithuanian, Jonas Rauba, was convicted and discharged on a charge of being drunk and disorderly. An Estonian, Kaljo Murre, faced the same charge and received the same sentence. Murre claimed that this was the first time he had drunk beer and it would be the last time. These may well have been “famous last words”.

The Bonegilla camp was meant to be dry, although Ann has heard of smuggling and alcohol being allowed for special occasions, like Christmas celebrations and weddings. If the fruit growers were paying their men a fortnight in arrears, which has been the custom in Australia for a long time, then they would have had their first pay just before the 14-15 February weekend. It’s now wonder then that 3 were found in public places to have overindulged. No doubt more drinking went on that weekend in private.

Easter 1948 ran from Good Friday on March 26 to Easter Sunday on March 28. The day before Easter started, the Shepparton paper ran a paragraph headed, Balts on Move (see below).

As for the “itchy feet”, another 23 had returned to Bonegilla before Easter, making 36 in all, but more than 80 per cent were still on the job.

The bulk of the Baltic fruit pickers returned to the Bonegilla camp between 31 March and 7 April, 114 of them. Another 38 returned on 10 April, leaving one stalwart behind.

Borisas Dainutis did not get back to the Bonegilla camp until 5 May, so he seems to have spent nearly another 4 weeks with Messrs Turnbull Brothers of Ardmona. As he was sent then to the Dookie Agricultural College in Victoria, perhaps he was displaying a great interest in agriculture despite having been selected in Germany has a potential builder’s labourer. Let’s see what we find when we explore his life story soon.

|

A Turnbull Brothers fruit box saved by Cartonographer (Sean Rafferty)

Source: https://ehive.com/collections/5682/objects/939087/turnbull-brothers-orchards |

On the day that Borisas returned, another rural newspaper, the Riverine Herald, ran an article headed “Balts Appreciated”. Based on interviews with fruit growers, the Herald estimated that the fruit pickers had saved the Goulburn Valley the loss of thousands of pounds worth of fruit. “Proof of success of the scheme … (was that) the fruitgrowers (sic) were already voicing their wishes to participate in allocations of migrants next season”.

The fruit growers had not been happy with the front page publicity achieved by Razvidauskas, Kauba and Murre. The Herald said that, “Expressing disappointment that adverse publicity had been afforded the very small minority of the men who had clashed with the law during their sojourn in Tatura and Ardmona district, … the men were excellent types on the whole and proved themselves highly adaptable to a variety of work.”

There was a sting near the tail of the report: “It was further claimed that while some instances of difficulties in handling the Balts had been reported, on the average, where reasonable conditions were provided for them, good service had been given.”

What did these fruit growers expect from young men who had just endured 5 or more years of war, sometimes right in the middle of it, digging trenches between the opposing German and Russian sides? All had been living on restricted rations until they boarded the Heintzelman and therefore were not at their healthiest. There should be no need to mention also that some of them were more highly educated than most of those making a career of fruit growing and so might have regarded fruit picking as yet another obstacle on the path to a more satisfying future.

SOURCES

National Archive of Australia: Migrant Reception and Training Centre, Bonegilla [Victoria]; A2571, Name Index Cards, Migrants Registration [Bonegilla] (1947-56); https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/DetailsReports/SeriesDetail.aspx?series_no=A2571 accessed 17 May 2025 ("Bonegilla cards").

National Archive of Australia: Migrant Reception and Training Centre, Bonegilla [Victoria]; A2571, Name Index Cards, Migrants Registration [Bonegilla] (1947-56); LAURINAVICIUS POVILAS, LAURINAVICIUS, Povilas : Year of Birth - 1908 : Nationality - LITHUANIAN : Travelled per - GENERAL HEINTZELMAN : Number – 571 (1947-48) https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/ViewImage.aspx?B=203619595 accessed 17 May 2025.

Riverine Herald (1948) 'Balts Appreciated', Echuca, Moama, 5 May, p 2 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article116540389 accessed 13 June 2025.

Shepparton Advertiser (1947) 'Baltic Migrants For The Fruit Harvest, Most Will Work at Ardmona', 12 December, p 1 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article173900200 accessed 13 June 2025.

Shepparton Advertiser (1948) 'Labor Problem for Fruit Harvest' 6 January, p 1 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article169556903 accessed 2 June 2025 accessed 2 June 2025.

Shepparton Advertiser (1948) 'Baltic Migrants Arrive' 30 January, p 1 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article169557378 accessed 2 June 2025.

Shepparton Advertiser (1948) ‘Balt Fights Three Police’ 17 February p 1 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/169557746 accessed 17 June 2025.

Shepparton Advertiser (1948) ‘Balts on Move’ 25 March, p1, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/169558516 accessed 17 June 2025.

Sun News-Pictorial (1948) 'Wild After Wine, Balt Fined', Melbourne, 17 February, p 10 , http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article279326226 accessed 2 June 2025.

Tribune (1948) 'Balts Work 48 Hrs. For 40 Hrs. Pay', Sydney, 14 April, p 3, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article208109382 accessed 13 June 2025.

%20%2019471203%20p%205%20edit.jpg)